WHEN RICHARD FLORIDA burst onto the North American scene nearly 20 years ago, he did so with a sunny urban vision.

His breakthrough book, The Rise of the Creative Class, asserted that a growing class of knowledge workers, techies, artists, and other creative people was gravitating toward city districts that offered “a vibrant ‘quality of place.’” He believed that as these talented folks settled into locales that welcomed diversity and contained great restaurants, pedestrian-friendly streets, bike lanes, and other appealing features, a “more inclusive urbanism” would take root.

Over the past several years, however, Florida, director of the University of Toronto’s Martin Prosperity Institute for the past decade, has turned gloomy, churning out studies and commentaries warning about worsening disparities in the cities where most of the high-paying creative jobs are concentrated.

Now his darkening view is elaborated on at book length in The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can Do About It (Basic Books, 336 pages, $28 hardcover). “As I pored over the data,” Florida writes, “it became increasingly clear to me that only a limited number of cities and metro areas, maybe a couple of dozen, were really making it in the knowledge economy.”

The encouraging news—to the extent that Florida delivers encouraging news any more—is that demand for lively, walkable neighborhoods is burgeoning in the US and Canada. The creative sector is strong, and Florida reports that “the advantaged knowledge workers, professionals, and media and cultural workers” earn more than enough to live in pedestrian-friendly, amenity-rich urban settings.

The converse, he says, is that “members of the two less advantaged classes—blue-collar workers and service workers in jobs like food preparation and office work”—are being left out. Those two classes have lost economic ground when the price they pay for housing is taken into account. Increasingly they cannot afford to live near the vital hubs of the knowledge economy. In New York, the average creative-class worker has $71,245 of annual income left over after paying for housing, but the average working-class person has only $27,343 left over and the average service-class worker has a mere $17,861. No wonder inequality has become one of the pressing issues of our time.

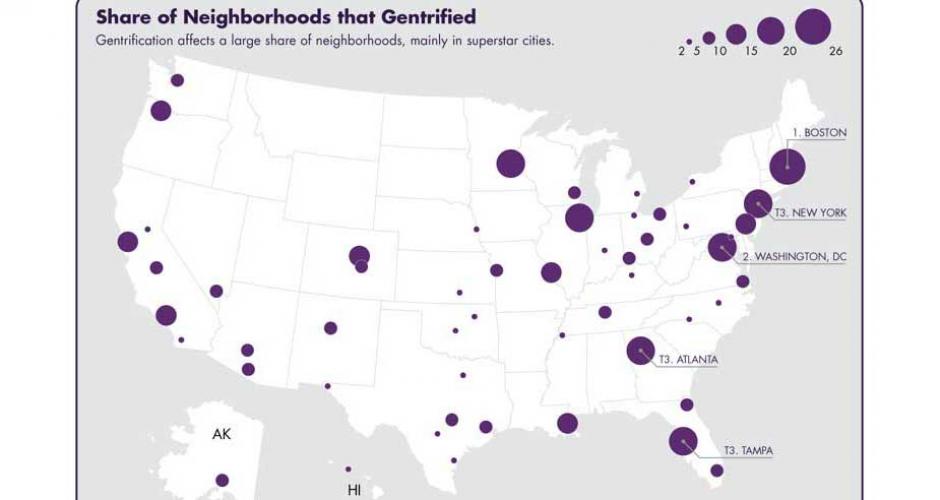

The clustering of talent and economic assets in cities is benefiting “the already privileged, leaving 66 percent of the population behind,” Florida says. “Left unchecked, this clustering force generates a lopsided, extremely unequal kind of urbanism in which a relative handful of superstar cities, and a few elite neighborhoods within them, benefit while many other places stagnate or fall behind.” (review continues at Public Square)